How Bernie Sanders is cultivating California for 2020

Bernie Sanders can’t get enough of California.

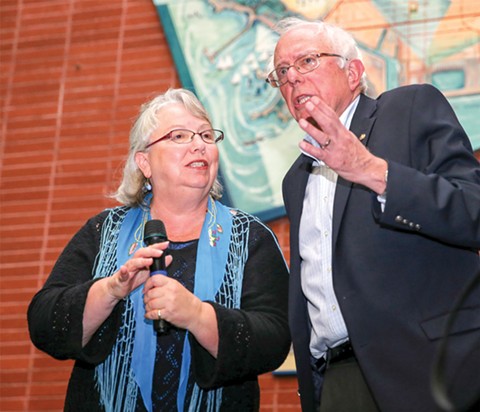

Sanders, the independent senator from Vermont, barnstormed the Golden State ahead of the June 2016 primary like no presidential candidate in recent memory. The front-runner in the party’s nascent 2020 field has returned regularly to campaign for a drug price initiative and to urge support for a universal health care bill similar to one he’s proposed in Washington. His next public event comes Friday in San Francisco at the invitation of the nurses union, among his most vocal supporters.

[...]

Before formally launching his 2016 presidential campaign, he appeared at a community event in the East Bay and endorsed a trio of candidates for local office, including Gayle McLaughlin, who was terming out as Richmond’s Green Party mayor and running for the City Council.

“It was a real solidarity moment for us,” said McLaughlin, now an independent candidate for lieutenant governor who won’t take corporate money. “It showed to me that there was support for Bernie Sanders in the Bay Area.”

Another new voice was Gayle McLaughlin the former mayor of Richmond, whose recent experience is chillingly relevant to San Pedro.

“Rancho LPG stores 25 million gallons of very explosive and flammable propane and butane gases and there’s no way possible to make these tanks safe,” McLaughlin said. “I speak from some experience. I was serving as mayor of Richmond, Calif. when in August 2012, the local Chevron refinery exploded, and burned for many hours, sending 15,000 people to local hospitals; 19 Chevron refinery workers barely escaped with their lives.

“Years before the fire, Chevron ignored safety demands from the people in city government of Richmond. They gave the same type of empty reassurances that the good people of San Pedro continue to receive from Rancho LPG — ‘It’s all fine and safe.’ Well, after the refinery explosion, Chevron pleaded no contest to criminal neglect and was mandated to initiate repairs for $25 million, mostly to replace corroded pipes they had refused to fix until now.”

The moral was obvious, she continued.

“It’s all too clear that corporations put profits before people, and companies like Chevron and Rancho LPG gamble with the safety and wellbeing of the community,” McLaughlin said. “Furthermore, too often our regulatory agencies have allowed and enabled these companies to do this gambling at our expense. The fact that other agencies have acted irresponsibly and granted permits to Rancho, and are allowing this disaster in the making does not relieve you, Lt. Gov. Newsom and members of the commission, of your responsibility to protect the lives of the people of California. Use the powers bestowed on you by the state of California to protect the people of California.”

Read the rest of the story at Random Length News

Highland Community News: Gayle McLaughlin for Lt. Governor

In 2010, as Mayor of Richmond, CA, I presided over our City Council when we unanimously passed a resolution to boycott the State of Arizona for its SB 1070 law which expanded statewide the massive racial profiling and gross human rights violations that Sheriff Joe Arpaio was leading in Maricopa County.

Six years later, in November 2016, the voters of Maricopa County succeeded in firing the infamous sheriff, and he was recently convicted of criminal contempt for violating a 2011 order that barred him from detaining individuals solely based on suspicions about their legal status. He had ignored this order for years continuing illegal ‘round-ups’ and raids and detaining individuals for further investigation without reasonable suspicion that a crime had been committed.

Trump, using his "divide and inflame" tactics, pardoned Arpaio last Friday. Trump threw gasoline into the racial fires. The nation is outraged and polarization has increased. I add my strongest condemnation to this pardon.

Rather than focusing on Trump and his playbook, I invite us to reflect instead on the long march of resistance, repudiation, organizing, and mobilizing that the citizens and residents of Maricopa county carried out, until last November when they successfully voted to reject Arpaio and his policies.

Many good people of Maricopa came together to attempt to recall Arpaio in 2007 and again in 2013. They failed to defeat him electorally on five occasions. But they organized better in 2016 by building coalitions. The “Basta Arpaio” coalition joined those supporting Proposition 206 to increase the state minimum wage. These mutually supportive campaigns went out knocking on doors, educating and registering voters. The good people of Maricopa won, even when Arpaio obtained as many votes in 2016 as he did back in 2000.

My campaign is a progressive grassroots organizing campaign, focused on organizing hundreds of new and existing corporate-free grassroots local organizations. There are important lessons for us in this story. People win with resistance, persistence, organizing, strategizing, building coalitions, not giving up, and embracing all those who want common goals.

Arpaio may have escaped this conviction, but the residents of Maricopa and Arizona have learned the path and the methods to achieve other victories for the people, and even perhaps justice for Arpaio’s crimes which include abuse of power, misuse of funds, racial profiling, failure to investigate sex crimes, improper clearance of cases, unlawful enforcement of immigration laws, and election law violations.

We learn from our experiences, we share our experiences, we build the tools to transform our lives and limit oppression in all its forms.

Today I join all people of good will and in particular our Latina sisters and Latino brothers throughout this nation and we say: This is not over. We want justice. We will organize to have it.

These Cities Are Putting Our Fractious Federal Government to Shame

Gayle McLaughlin led something of a revolution in the small, Bay Area city of Richmond, California. First elected to the mayor’s office there in 2006, McLaughlin and her leftist political organization the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA) transformed the city from a de facto company town dominated by the local Chevron refinery into a leading example of the power of progressive municipal politics. Over the last decade, the RPA defeated Chevron-backed candidates at the ballot box, implemented a $15 dollar minimum wage, fought foreclosures during the financial crisis, and, most recently, in 2016, passed the first rent-control law in California in years, among other achievements. The story of this grassroots political movement is one of the gems of the progressive urban renaissance.

Now McLaughlin wants to take RPA’s model and message statewide by becoming California’s next lieutenant governor. On July 18, she stepped down from her seat on the Richmond City Council and embarked on a multi-week tour of Southern California, visiting local progressive groups and rallying them behind her. Unaffiliated with any political party and vociferously supportive of single-payer health care, sanctuary-city policies, and free public college, among other issues, McLaughlin’s campaign hopes to draw on the Sanders-inspired enthusiasm for social democracy that has electrified leftists across the country. The election will take place in 2018.

“This campaign will give me a larger stage and a louder megaphone to get out the message about building local political power,” says McLaughlin. “That is the core message of my campaign: Build local political power in your cities and communities, like the RPA did in Richmond. If we could do it there, if we could get Chevron off our back, we can do it anywhere.”

By Jimmy Tobias

This country’s problems, everyone knows, started long before Trump and will outlast him too. In the United States, in 2016, before our current president took office, police killed at least 309 black people in cities across the country, the Mapping Police Violence project has reported. During the final fiscal year of President Obama’s tenure, federal enforcers deported more than 240,000 undocumented immigrants. A report out last year by the economist Thomas Piketty and his colleagues showed that US income inequality has continued to grow more severe. Private health care in this country is a laughingstock, and will get much worse if the GOP has its way. Our national parks are in disrepair, and our roads and bridges and highways are falling apart. We’re in the midst of a mass-extinction crisis. We’re at war. Climate change has arrived.

This article was produced in partnership with Local Progress, a network of progressive local elected officials, to highlight some of the bold efforts unfolding in cities across the country.

All of these are long-accruing, generational crises. They can’t be blamed on a single administration, no matter how violent and vile, no matter how racist and reactionary. Folks understand that fact. They act on it. And in the last month, as in the many months before, they have been busy, busy, busy: In small cities and huge metropolitan centers, in the heartland and the high plains and beyond, good people have mobilized against ongoing police violence, resisted the deportation state’s creeping authoritarianism, organized against plutocratic tax policies, and launched electoral campaigns with bold and radical platforms, among other promising progressive developments. These are people who, at this very moment, are working to clean up the systemic corruption that has beset us, and of which Trump is just a particularly grotesque consequence. Even last week’s sordid Scaramucci burlesque couldn’t distract them.

CHIEF JUSTICE

Hundreds of people took to the streets of Minneapolis on July 20 and 21 to rally, march, and protest against the killing of Justine Damond, who was shot in her pajamas after calling 911 earlier this month to report a possible rape. As the protesters marched, they called for justice for the multiple victims of Minnesota police violence.

Damond, a 40-year-old yoga teacher from Australia, is only the latest victim in a disgraceful catalog of police killings in and around the city in recent years. Exactly a year and a week before Damond’s murder, local police shot and killed Philando Castile, 32, a beloved figure at the elementary school where he worked, after they pulled him over as he returned home from grocery shopping. Police killed Jamar Clark, 24, in November 2015. In both Castile’s and Clark’s cases, the officers who pulled the triggers were not convicted of any crimes. No one was held accountable.

That could be changing, however. On the second day of protests against Damond’s murder, people blocked off a downtown light-rail station and then flooded into City Hall. When they arrived, Mayor Betsy Hodges was holding a press conference announcing the resignation of Minneapolis Police Chief Janeé Harteau.

The chief’s decision to step down, spurred as it was by potent public outrage, may not be enough. As the mayor made the announcement, indignant residents and organizers interrupted her. “We don’t want you as our mayor of Minneapolis anymore,” said activist John Thompson, a friend of Castile’s, according to The Washington Post. “We ask that you take your staff with you. We don’t want you to appoint anyone anymore.”

As cries of “bye-bye Betsy” filled the room, the mayor cut the press conference short.

SEATTLE’S TRUMP CARD

With excited onlookers holdings signs that read “Tax the Rich,” the Seattle City Council voted unanimously on July 10 to levy an income tax on the municipality’s wealthiest residents.

“Today our progressive city is boldly taking on our state’s deeply regressive tax structure—one that’s both unsustainable and unjust,” wrote Mayor Ed Murray on Twitter on the night of the vote.

Seattle’s decision to implement an income tax makes it the first jurisdiction in Washington to do so. No other city in the state, nor the state government itself, collects an income tax, making Washington’s one of the most regressive tax systems in the nation.

The new measure, which grew out of a grassroots campaign called “Trump-Proof Seattle,” will impose a 2.25 percent tax on individual incomes above $250,000 a year. It will also apply to married couples in the city making more than $500,000 a year. The tax is expected to boost Seattle’s budget by roughly $140 million a year, helping offset any financial harm that the Trump administration’s austerity agenda inflicts on the city.

REVENGE OF THE BACKPACKERS

For years, the state of Utah has led a right-wing assault on our federal lands, trying to roll back conservation protections and undermine public control over national forests, national monuments, wildlife refuges, and more. Among other priorities, the state government, as well as Utah’s congressional delegation, backed by dark-money groups tied to the Koch brothers, have sought to transfer millions of acres of federal land to the control of reactionary state and local governments across the West and open up these lands to increased oil and gas drilling. Their aim: to fundamentally weaken, if not destroy, one of this country’s greatest experiments in social democracy—namely, the 600 million acres of public land that belong to all of us and are managed on our behalf by the federal government.

Utah, however, is about to suffer for its plutocratic anti-public-lands agenda. On July 6, the massive outdoor-industry trade show Outdoor Retailer, which for years has hosted its twice-annual event in Salt Lake City, announced officially that it was relocating to Denver, Colorado. The show, which features products from companies like Patagonia, REI, and North Face, decided to leave Salt Lake City for one simple and very sensible reason: It opposes the state’s anti-conservation crusade.

In a statement released earlier this year, in which it previewed its intention to relocate, Outdoor Retailer explicitly tied its move to the “long history of anti-public land sentiment and action stemming from Utah’s state and congressional officials.”

Outdoor Retailer’s decision to make Denver its new home will bring Colorado (and cost Utah) roughly 85,000 visitors and $110 million a year in economic activity. The move, meanwhile, comes as conservation groups and public-lands enthusiasts across the country continue to rally, protest, and otherwise resist the reactionary campaign against public lands and conservation laws, including the Trump administration’s ongoing attempt to gut the Antiquities Act.

ICING OUT ICE

Immigration and Customs Enforcement has inspired fear in immigrant communities for a long time, threatening deportation and, all too often, acting on it. “But,” says Rebecca Kaplan, a City Council member in Oakland, California, “the degree to which they are explicitly being used to go after people who aren’t accused of any crime is way over the top now. They are being used as a tool of intimidation and fear.”

Particularly egregious, Kaplan says, are incidents of ICE officers going to schools to arrest people as they drop their kids off, or to courts to sweep upundocumented immigrants offering testimony or standing trial.

“This is a real threat to people’s safety, the behavior ICE is engaged in,” she adds. “It is important to make clear to the community that we will not collude in that.”

On July 18, the Oakland City Council decided it wouldcollude with ICE no longer when it passed legislation authored by Kaplan that officially cut the municipality’s ties with the federal deportation agency. The resolution terminated a memorandum of understanding the city made with ICE in 2016, during the Obama years, that enabled some local officers to cooperate with ICE agents operating in the area. The decision was meant to reinforce and strengthen Oakland’s commitment to being a sanctuary city.

And Oakland has company. Harris County, Texas, home of Houston, stopped cooperating with ICE in February in response to Trump’s amped-up attacks on immigrants. In March, Los Angeles barred its airport and port police from inquiring about peoples’ immigration status.

ALL PROGRESS IS LOCAL

More than 130 local elected officials from around the country arrived in Austin, Texas, in late July for the annual gathering of Local Progress, a nationwide network of progressive council members, mayors, and more that pushes for “a strong economy, equal justice, livable cities and effective government.” Larry Krasner, the civil-rights attorney running to be Philadelphia’s next district attorney, was there. So was Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, the young leftist member of Chicago’s City Council. Tishaura Jones, the St. Louis treasurer who ran a bold campaign to be the city’s mayor last fall, attended, as did Greg Casar, the Austin city councilman who has led the fight against Texas’s vicious anti-immigrant law SB 4. And there were many others as well—officials from Berkeley to Denver, from Indianapolis to Albany, from Flagstaff to Tacoma to Kansas City.

They came for panels and workshops and meetings on a range of topics, including discussions about strategies to resist Trump’s Department of Justice, fight back against right-wing preemption laws, and build renewable-energy infrastructure at the local level. They also came to protest. During the first day of the gathering, attendees marched to the Texas State Capitol to rally against SB 4, which imposes harsh penalties on cities and local officials that refuse to collaborate with federal immigration law enforcement in the state. Austin, among other Texas cities, has sued to overturn the law.

“Austin is the heart of the battle against SB 4,” says Helen Gym, vice chair of Local Progress and a Philadelphia City Council member. “We decided to gather in Austin just for that reason, because the city itself is a great example of a municipality rising to this political moment, coming up with smart strategies and responding to the needs of its community.”

THINKING LOCALLY, ACTING STATEWIDE

Gayle McLaughlin led something of a revolution in the small, Bay Area city of Richmond, California. First elected to the mayor’s office there in 2006, McLaughlin and her leftist political organization the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA) transformed the city from a de facto company town dominated by the local Chevron refinery into a leading example of the power of progressive municipal politics. Over the last decade, the RPA defeated Chevron-backed candidates at the ballot box, implemented a $15 dollar minimum wage, fought foreclosures during the financial crisis, and, most recently, in 2016, passed the first rent-control law in California in years, among other achievements. The story of this grassroots political movement is one of the gems of the progressive urban renaissance.

Now McLaughlin wants to take RPA’s model and message statewide by becoming California’s next lieutenant governor. On July 18, she stepped down from her seat on the Richmond City Council and embarked on a multi-week tour of Southern California, visiting local progressive groups and rallying them behind her. Unaffiliated with any political party and vociferously supportive of single-payer health care, sanctuary-city policies, and free public college, among other issues, McLaughlin’s campaign hopes to draw on the Sanders-inspired enthusiasm for social democracy that has electrified leftists across the country. The election will take place in 2018.

“This campaign will give me a larger stage and a louder megaphone to get out the message about building local political power,” says McLaughlin. “That is the core message of my campaign: Build local political power in your cities and communities, like the RPA did in Richmond. If we could do it there, if we could get Chevron off our back, we can do it anywhere.”

Lieutenant Governor Hopeful Gayle McLaughlin Wants to Take the East Bay’s Progressive Revolution to Sacramento

By Darwin BondGraham @Darwinbondgraha

The former city of Richmond mayor and council member hopes that the idealistic brand of politics she championed in the Bay will attract statewide voters.

Standing outside of Richmond City Hall, Gayle McLaughlin held up one end of a banner that read “homelessness is not a crime” while listening to someone deliver an impassioned speech against an ordinance outlawing sleeping outdoors on public property. It was 2002, and McLaughlin — a Chicago native who moved to Richmond the previous year —wasn’t wasting any time getting involved in local politics.

“Sleep is a human need,” she told the Express during an interview last week. “Unfortunately, our society so often criminalizes homelessness.”

No stranger to activism, McLaughlin grew up in a Midwest union family and took part in the Central American solidarity movement and the Rainbow PUSH coalition in the 1980s. But like a lot of progressives, the Democratic Party in the 1990s — recast by the Clintons into a more Wall Street-friendly organization — repulsed her.

In Richmond, McLaughlin joined the local Green Party chapter. One of the Greens’ priorities was reversing the new anti-homeless law.

They sent thousands of postcards to councilmembers demanding its repeal and held rallies before meetings, all in hopes that a more compassionate approach would prevail. But in the end, the anti-camping ordinance stood.

It was a bad year all around for Richmond. That May, the police department violently arrested two dozen people, nearly all of them Latino, who were celebrating Cinco de Mayo. Officers clubbed people with flashlights and batons and paraded them before the rest of the community in handcuffs.

To make matters worse, the city’s finances were falling apart. People were talking about municipal bankruptcy.

For McLaughlin, it was all a wake-up call. Appeals to reason and compassion fell on deaf ears. Other interests — raw, powerful “corporate” interests — prevailed. It convinced her that it wasn’t enough to just protest. At some point, you had to take power.

“We realized we needed to be the leaders we were waiting for,” McLaughlin explained.

Other Richmond residents were coming to the same conclusion. In a nut shell, that’s how the Richmond Progressive Alliance was born.

It seemed like the most unlikely place for the emergence of a new kind of left politics. A mid-sized, blue collar city where the political system was monopolized by candidates supported by the region’s major employer, Chevron, Richmond struggled for decades with industrial pollution, unemployment, high crime, police brutality, dilapidated housing, segregation, bad schools, and other urban ills. It was a hardscrabble town with few resources in the shadows of better-known progressive burgs like Berkeley and San Francisco.

But over the past two decades, Richmond turned into what some believe is the most progressive city in California. McLaughlin was very much at the center of this local revolution.

She’s now running for lieutenant governor, in hopes that the idealistic brand of politics she championed in the East Bay can gain a foothold in Sacramento.

McLaughlin is definitely an underdog in a race that’s already crowded with multiple contenders with far more name recognition. The odds she can win are slim. But then again, so were the odds when she first ran for council back in 2004, and for mayor in 2006. Across her political career, she’s always been able to pull surprising wins from obscurity.

But even if she overcomes the odds and gets to Sacramento, her platform involves radically reforming multiple third-rail issues that, common opinion has it, are insurmountable without massive compromises. Her critics say McLaughlin has been too rigid in ideology and unwilling to engage in the deal-making that’s required in Sacramento.

Undaunted, she told the Express that she’s running “a different kind of campaign.” She called it an organizing project, but added: “I’m in it to win it.”

In fact, she says it’s the necessary next step to advance Richmond’s progressive agenda. Without changing things at the state level, says McLaughlin, cities will continue running up against their own limits — no matter how many progressives they elect.

Defying the Odds

At first glance, McLaughlin seems like the most unlikely person to have played a central role in Richmond’s progressive upheaval. She exudes an even-keeled, calm Midwestern energy. She doesn’t have deep roots in Bay Area liberalism. When she talks, it isn’t in the fiery tone of a left-wing activist.

Andrés Soto remembers the first time he met McLaughlin at a mutual friend’s house. “I had never seen her before, never heard of her, she had no track record, and had just moved to town,” he recalled of the 2003 gathering at the home of Argentinian-in-exile Juan Reardon in November 2003. McLaughlin told Soto that she intended to run for city council.

Soto, a well-known East Bay native with ties to many social and environmental justice groups, had also decided to run for office. He and his two sons were among the people brutalized by the Richmond police during 2002’s infamous Cinco de Mayo riot.

“It became clear to me that if we were going to change the direction of the city, that meant we had to clean house with the city council,” Soto explained. “But we needed an organization.”

That organization was the Richmond Progressive Alliance. Their main source of strength was their ground game. Both campaigns had deep benches of energized volunteers ready to knock on doors and make phone calls. By late 2004, they were gaining traction.

Soto was surprisingly defeated that November, partly because the police union was successful in running negative ads against him.

McLaughlin, however, won a seat. The remarkable victory coincided with the beginning of the end for the old Chevron-dominated municipal politics. And it marked the start of McLaughlin’s rise as a progressive star.

“She defied the odds,” Soto said. “People began to identify with her, and say that, if a person like Gayle could do it, maybe they could do it to. So, she inspired others to run, get involved in campaigns, and get involved in the RPA.”

One of the first things McLaughlin set about doing was working to reverse the anti-camping law, but advancing the progressive agenda proved slow going.

By 2006, McLaughlin decided to run for mayor, as a Green Party candidate. Once again, she defied the odds and defeated the incumbent, Irma Anderson. As mayor, she appointed members of the RPA to various city boards and commissions. For example, Soto took a seat on the planning commission in 2009. Latino activists and RPA organizer Roberto Reyes took a seat on the police commission. And Marilyn Langlois, another RPA activist, joined McLaughlin’s staff and the planning commission.

Slowly, the city’s political structure was changing.

By 2008, the RPA had grown into a formidable organization. With McLaughlin as its de facto leader in the Mayor’s office, alliance member Jeff Ritterman won a council seat, and a measure to increase taxes on Chevron’s refinery was approved by voters.

The following decade proved that the RPA’s electoral strategy wasn’t a fluke. McLaughlin won a second term as mayor in 2010, and then, after being termed out, went on to win a seat on the city council again in 2014. It was a big year for McLaughlin and the rest of the RPA. Progressive candidates Eduardo Martinez and Jovanka Beckles also won seats on the council, and longtime conservative city councilmember Nat Bates lost to Tom Butt, a moderate liberal.

“If money equals a win, Chevron should have won in 2014,” Beckles told the Express. “They inserted three million into a city council election, but they lost because of people power and information.”

When asked to name the really big policy wins in Richmond over her tenure — coinciding neatly with the rise of the progressives — McLaughlin pointed to rent control, a higher minimum wage, and a reduction in crime.

McLaughlin was key in recruiting Chris Magnus, an openly gay police chief who made waves — and enemies — in the Richmond Police Department when he busted up the old boys club and promoted new leaders committed to community policing.

McLaughlin said she’s proud of stopping a proposed casino from being built at Point Molate, suing Chevron over environmental and safety issues, taxing the oil giant, fighting foreclosures, and having the city join one of the state’s nascent clean-energy authorities. The city also took steps to limit its police department’s interactions with immigration officials.

“Richmond has made an amazing turnaround,” said Beckles, who like McLaughlin is now trying to jump from city to state office. In May, Beckles announced her candidacy for the Assembly’s 15th District seat. “We’ve become more progressive than Berkeley. We’re the most progressive city in California.”

Soto said McLaughlin, more than anyone, personifies Richmond’s pragmatic style of coalition-building and progressive reform.

“I think the story of Richmond is certainly out there in a lot of activist communities,” he said, “and it may serve as a hook to get people to look at her, and potentially trust in her.”

Purity Over Results?

McLaughlin isn’t without her critics. And it’s not just Chevron and the landlord lobby that take issue with her political style and accomplishments.

Richmond Mayor Tom Butt believes that the fall of the conservative, business-dominated politics in Richmond was already well underway when McLaughlin and the RPA came on the scene in the mid-2000s.

“I think everybody who is not a part of the RPA is a little tired of hearing the story of how they rode into Richmond and single-handedly saved it,” Butt told the Express. “With or without RPA, Richmond has had a more progressive council over the past decade, and the majority of the council has been on the same page for most of the big issues.”

Butt said there’s been a revisionist trend in storytelling about Richmond, led by authors such as Richmond resident Steve Early, which portrays the RPA as a singular force of progress, when in fact many other people have been pushing a pro-environment and anti-corporate agenda locally as well.

Regardless of who gets credit for the greening of Richmond, Butt’s biggest critique of McLaughlin and her supporters has to do with what he characterized as their uncompromising commitment to principals — noble to a degree, but fatally flawed when it comes to seeking progress on vexing issues.

Butt said the RPA has been unwilling to listen to or negotiate with Chevron, landlord groups, the police union, and other opponents. Instead of holding any line, it’s actually stymied reforms, he argued.

“It’s better to get 50 percent of what you want rather than 100 percent of what you don’t want,” Butt said, paraphrasing a recent essay by Sen. Kamala Harris about the divide in the Democratic Party between the radical Bernie-crats and the more moderate bloc of voters who supported Clinton.

“I wish them the best of luck, but at the same time I worry that the movement she’s a part of will splinter the Democratic Party and peel off purist who won’t come back and support progressive candidates because they don’t meet their litmus test.”

Richmond Councilmember Jael Myrick is a lot like Butt: a progressive, but not a radical. He said he’s willing to negotiate with groups he sees as opponents, and to sign off on compromises if he thinks it’s ultimately in the best interest of his constituents. He also has been frustrated at times with McLaughlin and the RPA.

“Personally, she’s a warm and compassionate person, and she’s beyond reproach when it comes to her values,” Myrick said. But he added that McLaughlin has sometimes “put the need to take a stand above the actual people [she’s] supposed to be helping.”

The biggest example of this, according to Myrick, was the Richmond CARES program, which was supposed to use the city’s eminent-domain power to take over underwater mortgages on homes and then refinance them with private investors to prevent homeowners from being displaced. Myrick and Butt both said the program was created and approved by McLaughlin and the RPA to much fanfare, but that it never resulted in the restructuring of any loans. It was an idealistic stand that has had very little impact.

Meanwhile, Butt and Myrick say their negotiations with Chevron over its modernization project were opposed by McLaughlin and the rest of the RPA, but this resulted in a community benefits package worth $90 million.

“Politics and policy is so nuanced,” Myrick said. “There are times you have to plant your feet in the ground, but there are other times when you have to be willing to be flexible.” He said Richmond’s commitment to its sanctuary city status is one of those uncompromising stands he’s been perfectly willing to take alongside McLaughlin.

When asked if they agree with McLaughlin that it’s necessary for local progressives from Richmond and other cities to make the leap to Sacramento to change state laws and open up new possibilities for local legislators, both Myrick and Butt concurred.

As to whether McLaughlin stands a chance in the race for lieutenant governor, both of the Richmond politicians said “anything is possible.”

“We’ve seen so many predictions proven wrong,” said Myrick of McLaughlin’s underdog campaign. “In California, this might be a time when Gayle’s message connects more than ever.”

Progressives Take-On the Capitol

McLaughlin’s political philosophy is probably best defined by her oath to refuse corporate money for her campaigns. Instead, she and other RPA candidates only accept contributions from individuals. The position seems kind of gimmicky, but it was a result of the alliance’s stand against Chevron and the company’s favored candidates, which proved strategically powerful in Richmond. And as the nation lurched into the post-Citizens United era of dark money, this pledge has translated it into a more generalizable principal that resonates with wider audiences.

She and her supporters say that the pledge to go without corporate money builds trust and lets voters know that, after an election, their candidate won’t flip-flop on issues, or seek damaging compromises.

Her supporters also chalk her success up to strong social movements that work year-round to advance a progressive agenda. As RPA member Mike Parker wrote in a 2013 journal article: “RPA is not just about elections. We are year-round activists in the community and actively support other community organizations.”

This means that McLaughlin’s campaigns are different than the typical politician’s run for office. Rather than just delivering stump speeches at her own rallies, or schmoozing at exclusive events with donors, she goes out and marches with protesters or attends meetings of grassroots organizations. She says she wants to carry their work to Sacramento and translate it into policy.

Last Wednesday, McLaughlin was campaigning in Los Angeles, where she joined a march organized by health care advocates and that would end at Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon’s offices. The activists were calling for a revival of a state bill to establish universal, single-payer health care in California. On Thursday, she joined about 150 activists with groups such as the L.A. Tenants Union and the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment in a march to the offices of one of Los Angeles’ largest landlords in a low-slung building on Wilshire Boulevard.

“They have been evicting people,” McLaughlin said. “One woman was telling me that her rent is now is 70 percent of her income.” The protest, which included a mariachi band, then moved on to the home of Mayor Eric Garcetti.

“We need the mayors and legislators to hear us and enact rent freezes,” McLaughlin explained. “Housing is a human right, not a commodity.”

Although she’s run as Green Party candidate in the past, this time around McLaughlin isn’t hitching herself to any one organization.

“I think people should do what they think is best, work within or outside of a party,” she said, adding her “approach is to be a coalition builder,” and that she even supports “progressive Democrats who are fighting the good fight to reform the party.”

Her personal heroes remain radical outsiders, like Malcolm X and third party firebrands like Peter Camejo (Ralph Nader’s running mate in the 2004 presidential election and two-time candidate for California governor). But last year, McLaughlin switched her party affiliation from Green to no party preference, so that she could vote for Bernie Sanders in the state presidential primary. And Our Revolution, the political organization that sprung from the Sanders campaign and is continuing to support progressives in local and state races across the country, has been hosting meet-ups for McLaughlin as she tours the state.

It’s this interplay between outsider activists and politicians in seats of power that has characterized McLaughlin’s political career so far. But could she maintain ties to the grassroots left if elected to the statewide office of lieutenant governor?

The office itself has never been much of anything in California politics. It’s been mostly seen as a waystation to the governor’s office, not a place from which anyone can make much real change.

And if McLaughlin can manage, against huge odds, to gain recognition on the campaign trail and start polling as a real contender, it’s almost assured that Chevron, and perhaps even the California Apartment Association and other real-estate groups that fought rent control in Richmond, will pour money into a campaign against her.

Regardless of whether she can win, McLaughlin and other RPA activists say moving to state-level offices is the necessary next step for the progressive movement that emerged in Richmond more than a decade ago. Its leaders need to jump to the statehouse and create new possibilities for even more change.

“We’ve seen that a lot of state law supersedes what we’re trying to do in Richmond,” said Beckles, referring specifically to the limits of the city’s recently enacted rent-control law. “So, we need to get seats at the state level to change things.”

As one example, both Beckles and McLaughlin said they’ll work for a repeal of the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act if they have a voice in Sacramento. Doing so would allow cities extend rent-control protections to thousands of more units.

McLaughlin pointed also to the recent cap-and-trade legislation signed by Gov. Jerry Brown as an example of how powerful interests in Sacramento are doing exactly the opposite. She said while the new law might reduce greenhouse-gas emissions at the state-level, it actually will make pollution in places like Richmond worse, because it cuts off the ability of local air quality boards to regulate refineries.

“I will raise this issue on the state level,” she promised. “We need better state policies for cities that have refineries so we aren’t left with these outrageous levels of asthma and other illnesses.”

But then, she added that, true to her Richmond progressive roots, she can’t do it alone, and she expects activists to keep up the pressure, especially if she wins office.

“Just electing the right people to office is enough. I don’t think that’s the best way to go about things.”

SF Chronicle: Richmond’s Gayle McLaughlin running for lieutenant governor

On Tuesday, Gayle McLaughlin will step down from the Richmond City Council.

The next day, she and her husband, Paul Kilkenny, will leave for a 10-day road trip that will take them through Southern California and back. They’ll make stops in San Diego, Los Angeles and other cities, but it’ll be no summer vacation.

No, the work for McLaughlin, who is running for lieutenant governor of California, is just beginning.

Gayle McLaughlin: Richmond’s Grassroots Trailblazer Has Her Eye on State Capitol

by Keisa Reynolds

Richmond City Council has entered a new era without Councilwoman Gayle McLaughlin. The former mayor stepped down on July 18 to focus on her campaign for lieutenant governor of California.

McLaughlin, who says she wants to “take back the capitol for the people,” will be running against a batch of candidates including California State Sen. Ed Hernandez and Pakistani-born doctor Asif Mahmood in the 2018 election to replace Gavin Newsom.

A founding member of the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA), McLaughlin is internationally known for her two consecutive terms as mayor of Richmond in 2006 and 2010 as a registered Green Party candidate.

She relocated from her hometown of Chicago to Richmond with her husband in the early 2000s. It didn’t take long before she became involved in local politics.

McLaughlin was first elected to the Richmond City Council in 2004, then as mayor of Richmond in 2006. With the new title, she took on one of the most pressing tasks: fixing Richmond’s reputation. Richmond is far from being crime-free, but its place on the list of Most Dangerous Cities in America dropped significantly during her terms. The city also became known for its grassroots organizing.

Steve Early, journalist and author of Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City, considers McLaughlin a trailblazer—a term fitting for the grassroots-focused politician who helped bring on progressive city council members.

“Gayle’s role is absolutely essential to local movement building, public policy initiatives, and transforming the way that the mayor’s office operated, and encouraging other people to [pursue] city government in elected and appointed roles. That’s definitely part of her broader legacy,” explained Early.

“She shook up Richmond’s defeatism, the long-term prevalent fatalism that told us for decades we could not live better,” said Juan Reardon, McLaughlin’s campaign manager. “She led the progressive transformation of Richmond.”

McLaughlin and Reardon met in 2003 shortly after McLaughlin wrote a letter to the editor of West County Times about California gubernatorial candidate Peter Camejo, who was another Green Party politician. Together, they worked on social issues including decriminalization of homeless people and rights of day laborers. McLaughlin and Reardon, along with several other Richmond residents, went on to found the Richmond Progressive Alliance around the same time of McLaughlin’s first campaign.

In the 2016 election, RPA helped secured a supermajority, with five out of seven council members operating as corporate-free progressives.

Richmond Progressive Alliance and McLaughlin are nearly synonymous. However, the councilwoman is also lauded for her willingness to work with others in the interest of the people.

She gave up Green Party status to vote for Bernie Sanders in the presidential primary election as an independent voter—a move that signified her commitment to work for the people regardless of political differences.

Mayor Tom Butt speaks highly of McLaughlin but cautions giving credit to RPA for Richmond’s transformation in the last decade.

“One thing Gayle and the RPA are truly good at is getting elected. They are also good at taking credit, whether they earned it or not,” wrote Mayor Butt in an email to Richmond Pulse.

He noted that City Manager Bill Lindsay was the one who selected and hired former police chief Chris Magnus. Part of the city’s transformation was its reduction in homicide, an accomplishment attributed to the community-policing model implemented by Magnus.

Despite tensions between RPA and Mayor Butt, who succeeded McLaughlin in 2014, the two were able to find common ground and allies in each other during her tenure.

“At the end of the day,” he said, “McLaughlin and I have agreed on about 95 percent of public policy issues that have come before the City Council.”

Meanwhile, some residents wonder whether McLaughlin’s resignation from city council is really beneficial to the city or is simply a strategic move to keep RPA’s supermajority.

“I’ll miss Gayle personally, but right now on the City Council, I see her more as one more RPA vote, rather than an independent vote,” said Ellen Seskin, a Richmond resident.

“By leaving when she does, the council will have to choose her replacement before the election,” she said. “The RPA has a solid majority on the council, and they want that majority to first appoint Gayle’s replacement, certainly another RPA member, and still have a majority to choose Jovanka [Beckles]’ replacement, should she win.”

Beckles, another RPA council member, is running for California Assembly in District 15. She and McLaughlin are part of a growing trend of progressives seeking higher positions of office. Former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders is an inspiration, but RPA’s model of organizing has been a driving force for many.

Richmond resident David Schoenthal was appointed by McLaughlin to the Richmond Economic Development Committee. Schoenthal says that while he appreciated her focus on fighting for the less fortunate, he also saw her as someone whose ideological interests often superseded core issues of fixing services or jumpstarting economic development.

“I appreciated her willingness to step up and work on important human rights issues,” he said. “I would have liked her to focus more specifically on infrastructure and economic development for the long-term future.”

Progressive political circles around the country have touted McLaughlin’s work with RPA and the city council as the “Richmond Model.” The model emphasizes political campaigns run by grassroots organizers with the goal of creating a sustainable progressive presence in local government.

In the race for lieutenant governor, McLaughlin is once again a corporate-free candidate. Dubbed “Bernie Sanders of the East Bay,” she has said she will not accept corporate donations for her campaign for lieutenant governor.

Her campaign began with a 10-day road trip through Southern California, to spread the message of the “Richmond Model” and work with Californians to get corporations out of politics.

Lieutenant Governor Candidate Gayle McLaughlin in San Diego

July 19, 2017 (San Diego)—Gayle McLaughlin, former mayor of Richmond, California, says she’s running a corporate-free progressive campaign for Lieutenant Governor of California. She will hold a town hall meeting to discuss her campaign on Thursday, July 20 at 7 p.m. at the IBEW 569 hall, 4545 Viewridge Avenue, Suite 100 in San Diego.

According to a press release issued by the campaign, as a two-term mayor of Richmond, Gayle led a successful grassroots movement to “liberate the city from corporate giants and wealthy special interests. Her progressive leadership returned political power to the city’s residents and local businesses, defeating Chevron’s attempts to buy democracy.”

McLaughlin states, “Corporations have all the advantages and too much influence in California government. That has serious consequences for our cities, communities, counties, schools and hospitals. Corporate perks starve regular working families of the resources they need. As Lieutenant Governor, I will support the people’s struggles, work to build progressive coalitions, promote new policies, and mobilize all Californians of good will, regardless of partyaffiliation, who are willing to transform our state.”

Her town hall discussion will include:

• Her experience as a progressive Mayor - how she passed progressive

legislation in spite of Chevron’s money and power;

• Her Richmond Progressive Alliance experience and her views on a need for local unity of all progressive forces;

• Why corporate money is “toxic and addictive” and “how CA can get clean and sober”; and

• Why she is running for Lt Governor.

For more information, you can visit her website: http://www.gayleforcalifornia.org/

Progressive Candidate Gayle McLaughlin Speaking in San Diego

From Our Revolution North County

Progressive activist Gayle McLaughlin, running for Lieutenant Governor of California as an independent, will be speaking in San Diego on Thursday, July 20 at the IBEW 569 Hall.

As a two-term mayor of Richmond, California, McLaughlin and her allies were responsible for the passage of progressive legislation, including:

- an increased minimum wage, currently at $12.30 per hour

- California’s first new rent control law in 30 years

- creation of a municipal ID as a way to defend immigrant families

- increasing the powers of the Citizens Police Review commission to ensure accountability

The Richmond, CA story (Population 107,000) should serve as a primer for progressives nationwide on what is possible with coalition building and grassroots organizing. McLaughlin was a founder of the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA), a nonpartisan progressive group in western Contra Costa County, composed of members of the Green Party, Democratic Party, and the Peace and Freedom Party, as well as independent voters.

During McLaughlin’s term, voters defeated initiatives sponsored by Chevron, which has a refinery in the city, to the tune of millions of dollars aimed at undermining her leadership. After a fire at the refinery sent 15,000 residents to the hospital, the city sued the company for damages.

The city’s murder rate fell by 75%, and she made headlines nationwide for promoting the threat of eminent domain to force banks to modify bad mortgages, keeping people in their homes in the wake of the last recession.

The McLaughlin administration’s rise and legacy is chronicled in ‘Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City,’ published earlier this year with a foreword written by U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders.

Last year McLaughlin changed her political party registration from Green Party to NPP (“No Party Preference”) so she could vote for Bernie Sanders in the California presidential primary.

Now she is running as an independent candidate for Lieutenant Governor. Following her two terms as mayor and time as a Richmond city council member, McLaughlin tells supporters she realized there were problems facing Richmond and other California cities that were too big to solve at the city level.

She says her campaign goals continue to reflect her alignment with progressive ideals and aim to expand on her successes in Richmond. As a corporate-free candidate, she McLaughlin wants to get close to every voter “who has soured on the antics of our increasingly corporate-led political parties”, regardless of that voter’s party affiliation.

Her campaign is focusing on issues such as single-payer healthcare, the underfunding of schools due to Prop 13, repealing Costa-Hawkins to allow rent control expansion, and continuing to ignite the progressive movement within 100 California cities.

Our Revolution North County San Diego Meeting

With Speaker Gayle McLaughlin

"Corporate Free" Candidates Moving Up

Since 2004, members of the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA) have won ten out of the sixteen city council and mayoral races they have contested in their majority minority city of 110,000.

Last November, progressives gained an unprecedented “super-majority” of five on Richmond’s seven-member council—despite more than a decade of heavy spending against them by Chevron Corp. and other big business interests. For 12 years, RPA candidates have distinguished themselves from local Democrats by their lonely, Bernie Sanders-like refusal to take corporate contributions.